A Survey of Children’s Books Featuring Muslim Filipinos

by M. J. Cagumbay Tumamac (Xi Zuq)

In the last decade, the number of children’s books featuring Muslim Filipinos significantly increased, with most of these involving themselves as creators. These books highlight the diverse cultures of around 7 million Muslim Filipinos, who are mostly living in the autonomous region of the Bangsamoro. The name of the region means ‘the nation of the Moro,’ a term used by many Muslim Filipinos on the island of Mindanao, the Sulu archipelago and Palawan to assert their socio-historical identity.

Decades of Dearth

This was not the case for most of the history of children’s books in the Philippines, where only a few titles featuring Muslim Filipinos were published. In a list of children’s books from the regions compiled by Aklat Alamid, for example, there were only around 20 titles featuring Muslim Filipinos from 1990 until 2012. These books were authored by non-Muslim Filipino creators. Likewise, a majority of these titles are retellings of folklore.

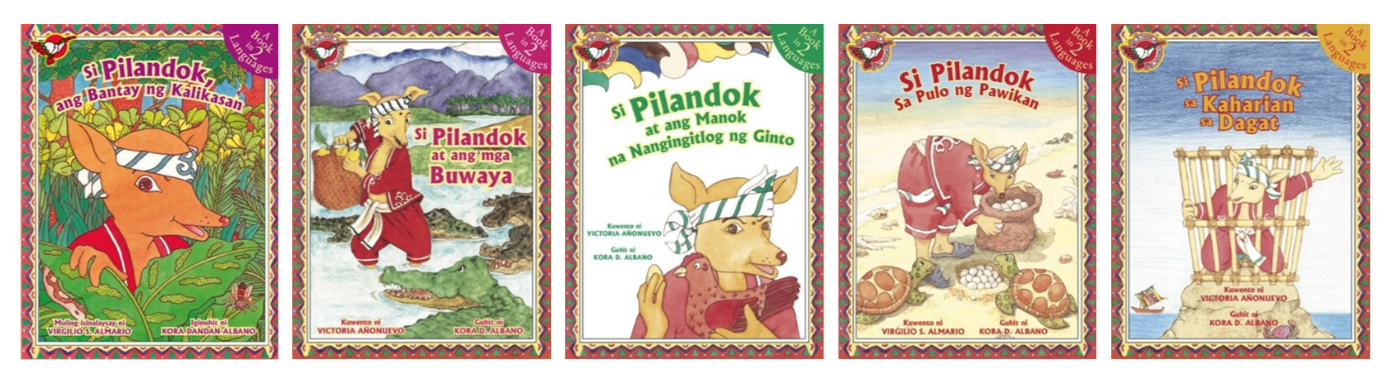

A popular example of these titles are the storybook adaptations of the adventures of Pilandok, a trickster figure in the folktales of several Islamised and indigenous groups in the country. Five tales—Si Pilandok at ang mga Buwaya (1994), Si Pilandok at ang Manok na Nangingitlog ng Ginto (1995), Si Pilandok sa Kaharian ng Dagat (1998), Si Pilandok, ang Bantay ng Kalikasan (1998), and Si Pilandok sa Pulo ng Pawikan (2001)—were retold in Filipino by Virgilio S. Almario, illustrated by Kora Dandan-Albano, and published by Adarna House.

Another notable publication was A Sea of Stories: Tales from Sulu, a collection of five short stories written by Carla M. Pacis and published in 2000 by The Bookmark and the World Wide Fund for Nature-Philippines. The book showcases the colourful culture of the people in the Sulu archipelago and their strong connection to the environment. The stories were also released as separate storybooks in English and Filipino in 2011 and 2015, respectively.

There were also contemporary realistic fiction titles for children, such as Virgilio S. Almario and Kora Dandan-Albano’s storybook Bahay ng Marami’t Masasayang Tinig (Adarna House, 2002) and Eugene Y. Evasco’s young adult novel Anina ng mga Alon (Adarna House, 2002), which both describe the plight of Sama Dilaut children. Meanwhile, Mary Ann Ordinario and Joanne de Leon’s storybook My Muslim Friend (ABC Educational Development Centre, 2007) highlights a true story of friendship between a Christian and a Muslim living in Mindanao.

In Their Own Tongues

Looking again at Aklat Alamid’s list of regional children’s books, 2013 was the turning point in the increase of titles featuring Muslim Filipinos. From that year until 2023, over 100 such titles have been produced, with a significant portion now created with the involvement and contribution of Muslim Filipino writers, translators, retellers and illustrators.

One contributing factor for this was the implementation of Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE), a policy that required the use of early graders’ mother tongues starting in the school year 2012–2013. To implement this policy, reading materials in different languages, including those spoken by Muslim Filipinos, had to be produced. Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, for instance, released in 2013 Sandor B. Abad’s Panitikang Mëranaw: Mga Piling Alamat at Kuwento, a collection of Meranaw folk tales written in Meranaw and Filipino. They then issued in 2021 several titles in Maguindanaon, Sinama, Bahasa Sug, and Meranaw under their series of folklore monographs and MTB-MLE publications.

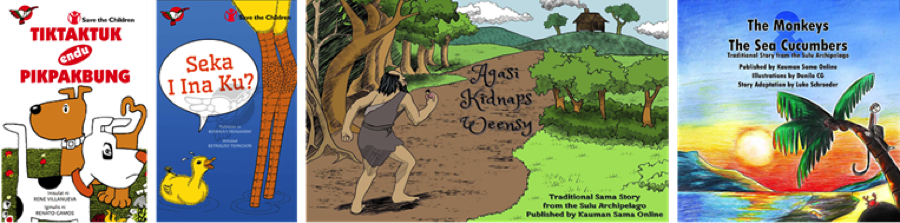

In 2015, Adarna House and Save the Children Philippines also published with limited distribution, Seka I Ina Ku? and Tiktaktuk endu Pikpakbung, the Maguindanaon translations of the picture books originally written in Filipino. Meanwhile, Kauman Sama Online, an initiative by linguist Luke Schroeder, partnered with government agencies and private groups to train Sama writers and illustrators to produce reading materials in the Sama languages. These stories are mainly accessible online and through a mobile application, but printed copies are also sold online and distributed to select Sama communities in Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago.

Stories of the Siege

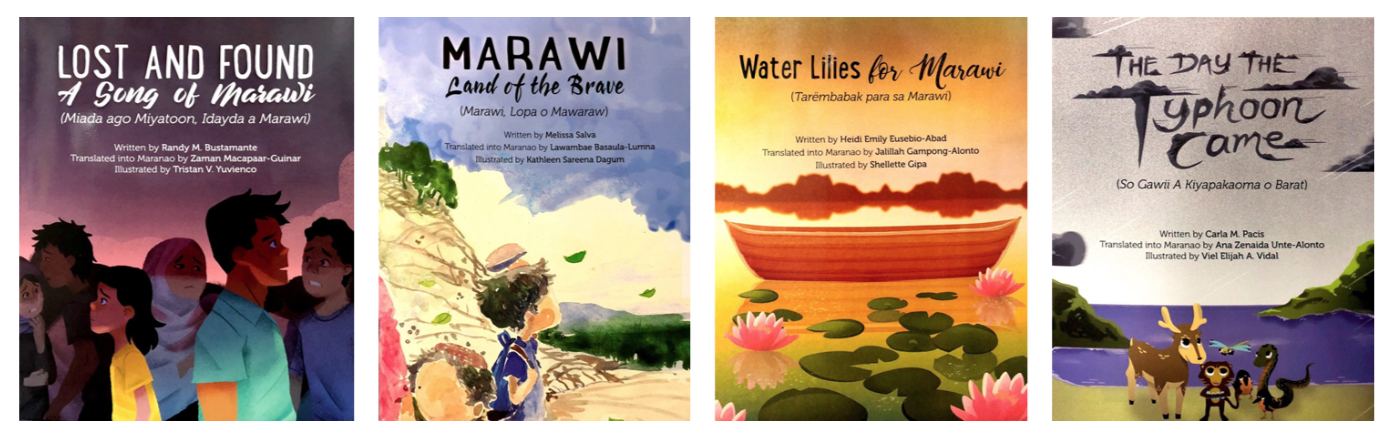

Another set of titles produced in the past decade was a reaction to the Marawi Siege, the armed conflict that devastated Marawi City in Mindanao in 2017 and affected millions of its mostly Meranaw residents. A year after the siege, for example, The Bookmark and the Philippine Business for Social Progress published four storybooks under the ‘iRead4Peace’ project. These were The Day the Typhoon Came, Water Lilies for Marawi, Lost and Found: A Song of Marawi, and Marawi, Land of the Brave. The books were a collaboration among the survivors who told their stories, non-Muslim Filipino creators who wrote and illustrated the books, and Meranaw language experts who translated the texts.

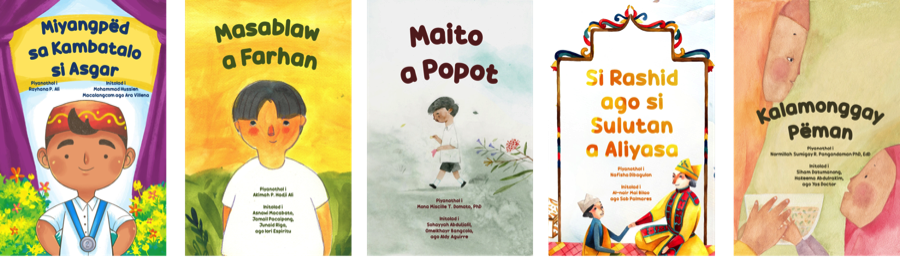

Save the Children Philippines and Plan International, in partnership with several organisations and the Education Ministry of the Bangsamoro region, also released in 2019 the following picture books written by residents of Marawi City affected by the conflict: Kalamonggay Pëman, Maito a Popot, Masablaw a Farhan, Si Rashid ago si Sulutan a Aliyasa, and Miyangpëd sa Kambatalo si Asgar. Produced under the project, ‘Pathways for Integrated and Inclusive Conflict-Sensitive Protection and Education for Children in Mindanao,’ the books were all written in Meranaw and featured Meranaw culture and Islamic values. The books were also authored by Meranaw writers, validated by experts on Meranaw culture, and co-illustrated by Meranaw children and established Filipino illustrators.

Three more titles by non-Muslim Filipinos also attempted to tackle the Marawi Siege, and these were Luis P. Gatmaitan’s chapter book, Maselan ang Tanong ng Batang si Usman (OMF Literature, 2021) and Mary Ann Ordinario’s picture books, A Basket in War (ABC Educational Development Centre, 2018) and Dearest Papa (ABC Educational Development Centre, 2018).

To More Productions

Besides picture books and storybooks, other forms of children’s books have been created in the past ten years. Examples of these are Catherine Torres’ young adult novel, Sula’s Voyage (Scholastic Asia, 2014); Borg Sinaban’s comic books Pilandokomiks: Ang Tatlong Sumpa (Adarna House, 2014) and Pilandokomiks: Mga Pagsubok sa Karagatan (Adarna House, 2015); and Tahanan Book’s folk song books, Kaisa-isa Niyan: A Maguindanaon Folk Song (2019) and Pok Pok Alimpako: A Maranao Folk Song (2022).

There have also been more titles authored by Muslim Filipinos produced and distributed for wider circulation. These include Sitti Aminah Sarte’s picture book, A Boy Named Ibrahim (Adarna House, 2014), Rogelio Braga’s young adult novel, Si Betchay at ang Sacred Circle: Ang Lihim ng Nakasimangot na Maskara (Balangiga Press, 2017), Virginia M. Villanueva’s folklore compilation, Tales from the Southern Kingdom (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2019), Nadira Abubakar’s nonfiction picture book, Lakbay Masjid (Adarna House, 2022), and Hanna Usman’s storybook, Si Jalal ago so Ranaw (Sari-sari Storybooks, 2023).

Lastly, the Education Ministry of the Bangsamoro region, the Department of Education, Australian Aid, Pathways and Adarna House organised from 2022 until 2023 one of the biggest book development projects that produced 32 picture books written and illustrated by creators from the region. The titles featured the experiences, beliefs, and culture of the people living in the Bangsamoro Region and were translated into their mother tongues.

Even though these books are still few in comparison to other book categories, the rise in children’s books that highlight Muslim Filipino experiences and are procuded with their involvement is a welcome development in the Philippine publishing industry.

--------------

(1) Aklat Alamid. “Masterlist of Books about/from BARMM,” electronic database. 31 January 2024 (latest update).

(2) Philippine Statistics Authority. “Religious Affiliation in the Philippines.” 2020 Census of Population and Housing. 22 February 2023.

(3) Kamlian, J.A., “Who are the Moro people?” Philippine Daily Inquirer. 20 October 2012.